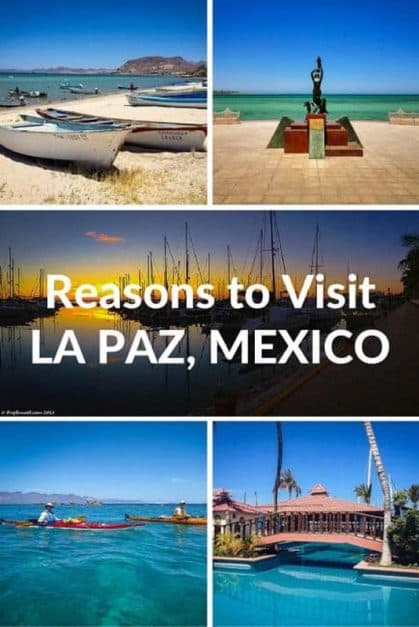

There are so many things to do in La Paz, Mexico. Located in the Baja Peninsula 100 miles from Cabo San Lucas in the southern tip of Los Cabos, La Paz is a beach lovers’ playground. With non-stop flights from Los Angeles, La Paz is a great weekend getaway for those on the West Coast of Canada and the United States.

Not to be mistaken with the other La Paz in South America, La Paz, Mexico is the capital of Baja California Sur. It is located on the West Coast of Mexico in a sheltered bay of the Sea of Cortez (Also known as the Gulf of California) These are the very best things to do in La Paz.

Table of Contents

Best Things To Do In La Paz, Mexico

There are only a handful of places that we’d consider living in this world, and La Paz, Mexico is one of them. By the time we had to fly home, we didn’t want to leave but never fear, we’ll be back. In the meantime, let’s check out all the reasons below we love La Paz, Mexico.

1. Sea Kayaking on the Sea of Cortez

One of the best things to do in La Paz, Mexico is to go Sea Kayaking on the Sea of Cortez. You can do day trips or multi-day tours. We took an amazing 10-day excursion with Baja Outdoor Activities to San Jose Island and it was pristine.

The turquoise waters of the Sea of Cortez were calm and crystal clear. We barely saw another soul during our expedition and had the most amazing time. It may have been a lot of work, but we also had a lot of fun.

There was also plenty of marine life encounters. Pods of dolphins swam by our group of 11 on a daily basis, we saw a whale, (and it isn’t even migration season) margaritas were flowing on the beach each evening and people spent their downtime snorkelling and hiking on the stunning coastline.

2. Kayaking Balandra Beach

If a 10-day kayaking trip isn’t on the agenda, Balandra Beach is a good spot to rent a kayak in La Paz. You can book day tours from La Paz to have a guided kayaking trip, or you can rent kayaks to explore its clear waters yourself.

It’s a lovely secluded cove tucked away from the open waters of the Sea of Cortez, so you don’t have to go far to have a great experience. You may also like: 15 Fun Facts About Mexico

3. Isla Espiritu Santo Island

If you love marine life encounters, Swimming with sea lions is one of the most uplifting things you will ever do in your life and you can do that in La Paz, Mexico! Isla Espiritu Santo is a UNESCO World Heritage list biosphere reserve.

We had the opportunity to swim with sea lions on several occasions and we never gave up the opportunity to jump in the water with them. One of the best things to do in La Paz is to see the sea lions.

You can take a boat tour on a panga (inflatable dinghies) to Espiritu Santo Island to see the sea lions less than one hour away.

Espiritu Santo Island has one of the most unspoiled ecosystems of the Sea of Cortez in Baja California Sur with white sand beaches, plenty of wildlife. Playa El Tecolote serves as a popular departure point for boat tours to Isla Espíritu Santo. Read more about Isla Espiritu Santo Island at An Unforgettable Adventure at Mexico’s Isla Espíritu Santo

Snorkel with Sea Lions

Visit the Los Islotes sea lion colony and see these playful creatures close up. You can also spy on sea turtles in Los Islotes. Los Islotes is a rocky outcrop that hosts a playful sea lion colony. Divers and snorkelers alike can interact with these curious creatures, making for memorable underwater encounters.

Swimming with sea lions is not allowed from June to August as it is mating season. You can book sea lion tours with GetYourGuide to Balandra Beach and Espiritu Santo Free cancellation with 24-hours notice.

4. Whale Watching in La Paz, Mexico

By far, one of the most popular things to do in La Paz is to go whale watching. And La Paz has no shortage of whales migrating through the area. Each year whales make their annual migration through Baja California. What makes La Paz so special is that the whales stop to have their calves and nurse in shallow lagoons.

Whale watching season is usually from January through April as whales migrate through the area. Sightings are almost guaranteed and many times they come right up to the boat and swim alongside the boat. It is definitely one of the best things to do in La Paz.

Blue Whale season is from March to July, Humpback whale season is February to June and Pilot whale season is October to February.

Suggested La Paz, Mexico Tours

Book a La Paz Whale watching tour with Baja Outdoor Activities in La Paz. They do day kayaking trips around the Baja Peninsula including multi day group and private excursions and kayak rentals. If you’re looking for the ultimate adventure in Mexico, They also offer Whale Watching, Yoga and SUP trips. Drop Ben an email to see what they can do.

5. Swim with Whale Sharks in La Paz

No trip to La Paz would be complete without swimming with whale sharks. Every year, whale sharks pass through to feed in the waters around La Paz from the beginning of October to the end of April. It is one of the best places in the world to see the world’s largest fish.

We swam with whale sharks in Cancun and it was one of the most magical experiences of our travels. La Paz isn’t as busy as Cancun, so we feel it would be a better place to swim with these gentle giants. Seeing a whale shark close up is magnificent. These gentle giants gracefully swim through the ocean effortlessly. It’s hard work keeping up to them, but it is an experience you will never forget. Book a La Paz whale shark excursion with Get Your Guide. 24-hour free cancellation and last minute bookings.

6. Go to the Beach

Just 15 minutes out of La Paz, you’ll find some of the best beaches in Baja California Sur. Many of the beaches are just north of La Paz. It’s no wonder we saw so many condos developing out of town. Baja City itself doesn’t have a beach downtown but it’s not far out of the city centre that you’ll find yourself in some beautiful stretches of sand.

There are many beaches around La Paz that are easy to visit:

- Balandra Beach

- Playa el Tesoro

- Pichilingue Beach

- Ensenada Grande

You can reach the beaches of La Paz by bus, motorbike or renting a car.

7. Go Off-Roading

Off-roading is huge here. So huge, that the Baja 1000 finishes in La Paz every other year. The nearby desert terrain is the perfect setting for off-road fun. With little civilization along the tracks, a person has hundreds of miles to fun to explore.

We had a taste of the off-roading experience during our drive to our launching off point for our kayaking trip to San Jose Island, and we can attest, it is some of the best off-roading we’ve seen outside of Mongolia.

8. Sandboarding the Sand Dunes

If the desert if your cup of tea, try a turn at sandboarding at El Mogote. It’s a ton of fun zipping down giant sand dunes on a sandboard. Trust me, it’s different than snowboarding, but it is worth giving it a go if you are an adrenaline seeker.

If you have trouble getting the hang of it, just lay on the board and use it as a toboggan. You can book sandboarding tours through Baja Desconocida.

9. Go Sailing

Sailing is a major activity in La Paz and when in Baja California, how can you not take a sailing trip on the Sea of Cortez? Book a sunset boat trip to look for wildlife and view the coast.

There is nothing better than sailing on the sea and the spectacular coastline of Baja California will take your breath away. Not to mention the spectacular sunsets.

10. Stroll Along the Malecón

Stretching 5.5 km (3.5 miles) from Hotel Marina – the hotel where we stayed in La Paz, there is a beautiful waterfront promenade known as the Malecón. There is nothing more romantic than taking a stroll around La Paz hand in hand with your honey admiring the street art.

Evenings are the best time to visit as the entire town of La Paz seems to come out to enjoy the cooler evenings. People bike, run and walk along the waterfront, stopping in restaurants for dinner or drinks and live bands play late into the night. It’s magical.

11. Paddleboarding – SUP

If any of you have been following for a while, you’ll know that Dave and I love paddleboarding and the Calm Waters of the Sea of Cortez are a good place to give it a try.

In La Paz, you can rent paddleboards and paddle along the shore. Or you can book paddleboarding trips and excursions with Baja Outdoor Activities located in La Paz.

If we could carry a paddleboard with us, we’d do it everywhere. I think that if we lived in La Paz, we would use our paddleboards for our commute. If we ever needed to go into town from our waterfront condo (I’m dreaming now) we’d just hop on our boards and paddle in.

12. Shopping in La Paz

La Paz is filled with jewelry makers and artists and there is a local co-op for artists, a walking street filled with street art and artists and various art shops throughout the town.

One of my favorite parts of visiting Mexico is to buy handmade necklaces and this trip was no different. We bought chains from street vendors and had them change them in front of our eyes to suit our taste.

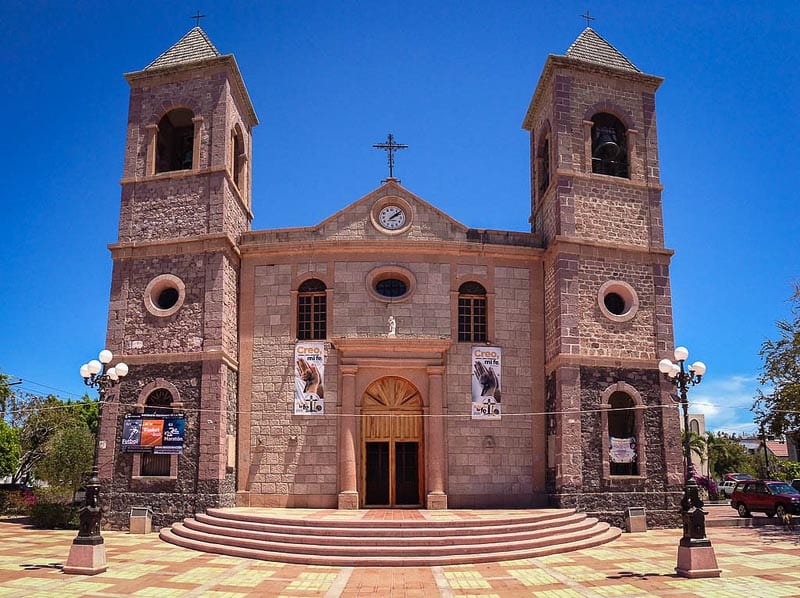

13. Cathedral of La Paz (Catedral de Nuestra Senora de La Paz)

Catedral de Nuestra Senora de La Paz is a lovely Catholic church located in the center of La Paz. It was founded by Jesuit Missionaries in the 18th century and the church was built in the 19th century. It stands where the original mission stood.

Visitors are welcome and can view Baroque religious symbols and enter for free!

14. Street Art of La Paz

The Malecon is filled with art and sculptures created by local artists. A lot of the art was also donated to help preserve the cultural heritage of La Paz.

Be sure to stroll along the Malecon, in the urban parks, the waterfront pier and into the city square. There are sculptures everywhere. You can read more about the sculptures of La Paz at Tenaja Holdings, a company that donated many of the pieces.

16. Explore the Marina

We stayed at the Marina Cortez located just a short walk out of downtown La Paz.

Marvel at the yachts parked at the marina and enjoy a stroll along the pier before settling in at one of the restaurants for a candlelit dinner at sunset.

Museums in La Paz

16. Whale Museum (Museo De La Ballena)

The Museo de la Ballena, or Whale Museum, is dedicated to promoting the understanding and conservation of whales and their marine environment. La Paz, being situated near the waters where gray and humpback whales often migrate, is an ideal location for such an institution.

The museum is devoted to educating visitors about the various species of whales, their life cycles, migration patterns, and the threats they face. Through a variety of exhibits, the museum sheds light on the evolution of these majestic marine mammals, their anatomy, and their vital role in marine ecosystems.

Beyond just education, the Museo de la Ballena is involved in various conservation initiatives. They often host workshops, lectures, and other events to raise awareness about the importance of marine conservation.

The Whale Museum of La Paz gives you everything you’ve ever wanted to know about whales. From their behavior and habitat to the evolution of whales and its impact on the local community.

Museo De La Ballena

17. Mining History Museum

A new museum that opened in 2018 located in the mountains of La Paz. Museo Ruta de Plata (The Silver Route Museum), traces the history of the area from the early settlers of the 1500s to the silver mining heritage from the 1750 – 1930.

Two more museums are in the works too! The Cowboy Museum and the Natural History Museum.

18. Playa el Tecolote

Playa El Tecolote is one of La Paz’s most renowned beach destinations, offering both tranquility and adventure to those who venture its way. Located just a short drive from the city of La Paz in Baja California Sur, it provides a refreshing escape from urban life and a chance to immerse oneself in the natural beauty of the Baja peninsula.:

Playa El Tecolote boasts long stretches of sandy shores that are perfect for sunbathing and leisurely walks. The crystal-clear waters and gentle waves make it a haven for swimmers and families.

The calm and clear waters are ideal for various water sports, including kayaking, paddleboarding, and snorkeling. The marine life is vibrant, giving snorkelers and divers a treat as they explore the underwater world.

19. Take a Kite Surfing Lesson in La Ventana Bay

La Ventana Bay, has rapidly earned a reputation as one of North America’s premier destinations for kite surfing. Its consistent winds, scenic beauty, and warm waters create a near-perfect environment for both beginners and seasoned kite surfers. Here’s a closer look at the kite surfing experience in La Ventana Bay:

Between November and April, La Ventana experiences steady northern winds, known as “El Norte,” which are ideal for kite surfing. These winds result from a temperature difference between the cold air from the north and the warm waters of the Sea of Cortez.

The bay’s steady winds and the lack of major obstacles make it a favorable spot for beginners but experienced kite surfers, La Ventana Bay offers challenging conditions further out in the sea, with bigger waves and stronger winds to test their skills.

20. Go Scuba Diving in the Sea of Cortez

Often referred to as the “Aquarium of the World”, the Sea of Cortez is home to a vast array of marine life. Whether you’re a beginner or a seasoned diver, the Sea of Cortez offers sites that cater to all skill levels.

The region has seen increased efforts in marine conservation, ensuring that its underwater treasures are preserved for future generations. As a result, divers often encounter thriving marine ecosystems. The underwater topography is diverse, with dive sites ranging from rocky reefs and sandy bottoms to underwater mountains and old shipwrecks.

21. Try the Chocolate Clams

La Paz is located on the sea, so it is no surprise that the seafood is fresh. One of the local delicacies is chocolate clams. The name “chocolate clam” doesn’t come from their taste but rather their appearance. The shell of this clam is a rich brown color, reminiscent of chocolate.

Chocolate clams, scientifically known as Megapitaria squalida, are one of the gastronomic treasures of Baja California Sur, especially in the La Paz region. These bivalves have become synonymous with the culinary traditions of the area. Chocolate clams are among the largest bivalve mollusks on the Pacific coast, sometimes reaching up to 6 inches in diameter. Their size combined with their delectable flavor makes them a favorite among locals and visitors alike.

22. End With a La Paz Sunset

Find yourself a beach, a sunset patio or just a place on the Malecon and enjoy the sunset. Nothing compares to the many sunsets we watched while visiting La Paz.

Being located on the west coast of Mexico, we had one extraordinary sunset view after another.

23. Where Eat in La Paz

Make sure you head out at night for some cocktails and nightlife. There are many great restaurants all over La Paz, ranging from small fish taco stands to fine dining.

Our favourite meal out was at Jonathan Roldon’s Tailhunter where we enjoyed coconut shrimp, fish tacos, fresh salsa, guacamole and the best margaritas we’ve had in years. It has been a staple in La Paz for 18 years and he also runs fishing charters out to the Sea of Cortez. It’s a place where we instantly felt welcomed and at home. Yet another reason why we think we could live in La Paz..

Hop on to discover the waterfront and stop in town for ice cream to cool off.

To find out more about travel to La Paz, Visit Baja Sur tourism to see all the Adventures in Mexico that await you on your next vacation.

Suggested La Paz Hotels

Hotel Marina – We stayed at Hotel Marina, it was a good affordable hotel, walking distance to town.cCheck out Availability & Prices on TripAdvisor / Booking.com

Costa Baja Resort – For a more upscale stay in La Paz, this is a highly rated choice. 20 minutes from downtown. Check out Availability & Prices on TripAdvisor / Booking.com

Why Visit La Paz?

La Paz is a laid-back town that has all the amenities you need. Filled with marine life and adventure, it has something for everyone.

La Paz, Mexico is growing quickly. Located just north of Los Cabos, it is a quieter vibe than the hectic tourist trap of Cabo San Locus. But Golf courses are springing up and eco-adventures are becoming popular.

Diving is a huge attraction and La Paz is a perfect getaway for the whole family. Jaques Cousteau once called the Sea of Cortez the Aquarium of the Sea and with good reason. You can have many unique wildlife encounters on and under the water.

La Paz is the perfect blend of a sleepy Mexican town with all the amenities of the big resort towns like Cabo San Lucas and Cancun. When we plan our next trip to Mexico, it’s going to be here for sure.

Plan Your Trip to La Paz, Mexico

Getting to La Paz, Mexico – La Paz is a two hour drive from Los Cabos.

Lonely Planet Mexico Travel Guide – We love traveling with our Lonely Planet guides. We go old school and use books, but LP offers apps, digital copies and even translation.

Google Translate App – If you want to immerse yourself in the culture of La Paz it’s good to practice Spanish. If you don’t know Spanish, get the app to help you speak the country’s language.

Universal Plug Adapter – This all in one adapter is great for all countries and you aren’t stuck with trying to find a different plug for each new destination.

Portable Water Filter – It’s important to stay hydrated when traveling in hot climates especially. Take care of the environment and fill up safely with the LifeStraw.

Flip Flops – You can’t go to the beach without flip flops. Tevas are comfortable and durable.

Our Adventure in La Paz Mexico was courtesy of Baja Outdoor Activities in La Paz. If you’re looking for the ultimate adventure in La Paz Mexico, drop Ben an email to see what they can do when you visit the Baja California Sur.

La Paz is located in the south of the Baja California Peninsula in the South Western State of Baja California Sur, Mexico.

The best things to do in La Paz is to Swim with whale sharks, go whale watching, kayak the Sea of Cortez and visit Balandra Beach.

Whale shark season in the Baja Peninsula is between October and April.

There are non stop flights from Los Angeles to La Paz or you can fly from other US hubs to Cabo San Lucas and then transfer to La Paz.

To find out more about travel to La Paz, Mexico Visit Baja Sur tourism to see all the Adventures Baja California Sur that await you on your next vacation.

They do day kayaking trips around the Baja Peninsula including multi-day group and private excursions and kayak rentals.

Enjoy this post on all the things to do in La Paz, Mexico? Save it to Pinterest for future travel planning.

Read more about travels to Mexico:

- Reigniting the Adventure in La Paz,

- Rio Secreto, Mexico’s Most Magical Cenote

- An Unforgettable Experience at Isla Espiritu Santo

- 25 Best Places To Visit in Mexico

- Best Things to do in Cancun, Mexico

- 10 Best Things to do in Mexico City for an Epic Trip

- 23 Amazing Things to do in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula

Great tips, thanks for sharing. Super fun read 🙂

La Paz seems great, can not waite to check it out! Thanks for sharing all your tips!

Looking forward to heading back to Baja in February! Haven’t been since I did my first Yoga Teacher Training there in 2007. This La Paz post is perfect timing since we’ll be doing a 1 week road trip through Baja Sur!

full name of the city was originally Nuestra Señora de La Paz (meaning Our Lady of Peace) in commemoration of the restoration of peace following the insurrection of Gonzalo Pizarro and fellow conquistadors against the first viceroy of Peru. La Paz is fast becoming a must-visit destination on the South American gringo trail, partly due to its convenient location between many of Bolivia and Peru’s greatest sites. The city was later moved to its present location in the valley of Chuquiago Marka.

Swimming with shark whales will be a lifetime experience i guess, i would do that despite the fact that i can’t swim

paddle boarding is not hard if you are relatively fit and have decent balance. The only time it becomes challenging is in ocean waves…its quite easy to fall off if its wavy. It’s also really simple to climb back on. on flat water its a cinch!

I paddle board up north in BC, Canada so falling into the water in Mexico would be pretty warm.

Definitely thinking about coming to La Paz! Met a cool friend at my new job. She’s been to La Paz and tells me it’s fantastic! I really want to go! I think I can make it happen one day too. Look for me, the girl with the big pretty hazel eyes!

I am interested in swimming with the Sea Lions. Have there been may issues with the animals biting people?

We haven’t heard of any. If you respect the environment and let them come to you, you’ll be fine. they are playful creatures, but don’t chase them or try to touch them. Just let them circle are you.

Hi Dave and Deb,

My name is Toni and I’m with Dwellable.

I was looking for blogs about the Baja of Mexico to share on our site and I came across your great post…If you’re open to it I would love to feature your story, please shoot me an email at toni(at)dwellable(dot)com.

Hope to hear from you soon!

-Toni F.

Thanks Toni, we’ll send you an email. We love Baja!

Hi Deb&Dave! I love your blog on La Paz. Gary & I have lived there for about 5 yrs now. Gary more so as he is retired, I’m still working.

We visited Cabo a few years ago and we loved the area so much we built a house in the hills off Tecelote Beach north of La Paz, Maravia Country Club Estates.

Stop by Palapa Azul next time you are in La Paz, Gary is there everyday after 2, November to April.

I found the best time to travel there is Oct-Nov or Mar-April.

Summer is way to hot.

Happy Trails to you!!!

LOVE IT!!! I’ve been to Loreto twice, and I m thinking La Paz this year. Whats the best time of year do you think? Loreto- August was way too hot- December was way too cold! I preferred August over December…thoughts? Great post!

We were there in April and it was starting to get by. I’d choose Feb/March

Awesome!! Thanks so much To Deb and Dave – it our was our GREAT pleasure to host your visit and we look forward to helping all your fans discover this amazing corner of the planet.

Many thanks

Team BOA

Blue sky, blue sea, the place is a paradise! I love to see La Paz Mexico!

Glad that there’s so much to see in La Paz. Hope to be there one week from now!

Just wondering re: a few things. You said that La Paz doesn’t have a beach downtown, but that you can reach some great ones by bus, etc. (15 minutes away). I’d love to spend a few days in the town of La Paz and to visit the local beaches during the day, but also want a few nights right on the beach itself. Is there a really nice one (lovely and not too crowded) that you highly recommend?

As for paddle boarding…I’ve never tried it, but might when I’m there. Looks like fun! 🙂

Great Article Deb and Dave, I am always surprised at how few people have heard of this amazing city. Having lived here for 2 years now, and visited for 8, it is somewhere I am so glad that I found!

Hey Lisa,

There are actually a few smaller beaches along the Malecon in La Paz, but as they are by the road they aren’t as tranquil as the beaches 10 to 15 minutes away by car.

There is however a beautiful little condominium and hotel on the beach 5 minutes out from town which unless you are staying there you might not think of going to because there isn’t much parking unless you are a guest.

It is called La Concha, and the condominiums are very reasonably priced especially for being right on the beach. We rent quite a few there and 60% of our guests come back every single year they love it so much.

Drop me an email if you have any questions, and I would be happy to help.

Simon.

Thanks for the information Simon, we may even look you up too! We’ve been considering wintering in La Paz ourselves. I think it’s the perfect spot in Mexico.

You can’t go wrong in Mexico, in my opinion. It’s why I’ve been here for going on three years now; there’s just too much to love…culture, views, people, relaxed lifestyle….I’d say go for the condo!

We just went sea kayaking in Greece and loved it! Stand up paddle boarding is next on our list to try.

We haven’t spent much time in Mexico, but La Paz looks wonderful.

Stand up paddle boarding is so much fun. If we find ourselves on a beach for an extended period this winter, we’re going to buy a couple of boards and use it as our workout. It’s a great core workout.

I have been to Cancun and Playa, although awhile back. I have never been to the Baja area. Looks like I need to give it a shot.

You will have to give it a shot. We had always gone to the other side ourselves. CAncun, Maya, Cozumel Playa Del Carmen etc. It’s only in the past couple of years that we’ve ventured to the other coast of Mexico and we’ve been wondering why we didn’t do it earlier! Love it here.

Dream trip!! Love all of the activities (go Baja Outdoor Activities!). Even though I live in the hottest place ever, I am longing for a tropical trip…

Coincidentally, someone was JUST telling me about La Paz tonight. I had no idea about this destination until now. Can’t wait to check it out myself!

Hi guys,

I came across this post while browsing the net. This is such a great post and experience .

I have never been to Mexico, but seeing how great the place is with your awesome photos, I might push through with my plan next year and that is to visit the place (crossing my fingers)! And I will specifically put this place in my list of “must see /go places”in Mexico. 🙂

I am actually involved in a website (createyourtravel.com) that is currently on its development process which will be focused mainly on giving information to Mexico travelers that will help them ease the planning. So I hope that when it is up and live , you’ll check it out and would love to share your experiences to our users.

Thanks Deb and Dave for sharing such an awesome post!

So glad we could entice you to go to Mexico. I’m curious how you can give advice to travelers to Mexico when you havent’ been there? Hopefully you’ll get there next year so that you can give them first hand information. It’s beautiful and make sure to add La Paz to your list 🙂

Wonderful list of things to do in La Paz for sure and they all look like great fun! I think I would enjoy the Sea Kayaking just for the beauty of that water alone…something I find hard to resist!

Can't wait to go. 🙂

I’ve heard lots of good things about stand up paddle boarding. However, I’ve read mixed reviews on it from being easy to hard. The waters look beautiful there so kayaking would be a lot of fun.

I see why you would live there. Beach alone is good enough I guess. It’s pristine for sure. Looks like there’s so much to do as well. Have fun guys!